« Happy birthday Dante Paci | Main | Argenta's fourth story »

March 6, 2017

"Your Cireglio"

YOUR CIREGLIO

This is another profile of people who are related to us. My source material is limited, and none of them are here to defend themselves, so the profiles may be a little biased. The profile here is of our most infamous and therefore our most interesting kin. But don’t lose heart, it’s not all darkness and jail time in the family tree. The one coming up next is the exact opposite.

Main street Cireglio

The first profile was ‘Happy Birthday Dante Paci’ based on one letter from his father, and a number of letters to Dante in Exeter, Pa. from his long-distance love Clara Bartoli back in Cireglio. In letter dated November 10, 1920, Clara tells Dante…”dunque non dire nulla di questo neppure ai tuoi a Cireglio ricorderai bene questi paesi come sono chiachieroni… “…so do not say anything about this to your Cireglio, remember these country people are gossips…”

The common thread is these people are all from the montagna Pistoia of Cireglio, the home town of both our maternal and paternal ancestors. So herewith is another one of “your Cireglio.”

THE LIPPI SAGA

Ettore Lippi may have been the first of our relatives to leave Italy. Often the immigrants stated on their ship’s manifest that they were going to America to work or live with a cousin. I suspect our some of our grandparents indicated Ettore as their contact.

Ettore was a first cousin of Argene Lippi Paci, Adamo’s wife (our great grandparents). He showed up here in 1902, and was naturalized in April 1905.

The fathers of Ettore and Argene were brothers. I’m writing these profiles to my cousins of my generation; when I describe how we are related it is from the position of my generation.

The fathers were Gustove and Luigi Lippi, our great, great grandparent’s generation. There were 7 men, and 2 women. That group (the great, great generation) was descended from Pietro Lippi and his wife Carolina Chelucci. Pietro’s father’s name, Oliviero Lippi, is all we have of him, and that’s as far back as the Lippi line goes for now.

The Ettore and Argene Lippi generation numbered 24 and they mostly lived in the Pistoia area. Ettore is the only one to come to America according to the genealogy sheet I have.

His wife, Palmira, and son August who was born July 8, 1900 in Cireglio, arrived in 1903.

This saga is about August Lippi, who, due to some quirk in his dna, jumped off the work-a-day track of most of our immigrant forefathers into the suit and tie world of labor unions. It’s a saga of constant conflict, deal making and narrow escapes; of a model citizen who rose to fame as the working man’s advocate only to fall victim to his own poor judgement in his personal affairs.

In the 1915 Pittston city directory, Ettore is listed as a miner, and his son August is a ‘driver’. At that time Giulio, Cino, Dante and Pacino Paci were living in a rooming house in Exeter. We don’t know if Ettore made the jump from miner into management or union business before he died in 1927, but it’s clear August did as he took an exam for the position of mine foreman in 1922, and two years later moved up to the influential position of chairman of the United Mine Workers grievance committee for the Pennsylvania Coal Co., one of several operators in the area.

That position expanded in the spring of 1927 to president of the general mine grievance committee of a collection of small operations called the Pa. hillside collieries. And in July was elected to the executive position of mine inspector of District 1 of the UMW.

The Scranton Republican - July 7, 1927

The 1920’s were a period of turmoil for coal miners around the state as various factions clashed over just who was going to represent the miners’ interests to the various coal mining operations. The factions often came to blows and sometimes matched Capone in Chicago with their violence.

In the spring of 1927 Lippi ran for secretary treasurer of district 1 of the United Mine Workers and won. His father, who died that November, lived to see his son’s success, a rising star with his picture in the local paper, and glowingly described as ‘having a wide circle of friends….success is predicted….elected with only the grievance committee experience’.

Now things heat up. January 1928, the Pennsylvania Coal Co. which employed about 10,000 men wanted to close some of their local unprofitable operations. The local union and their chapters representing those 10,000 was plagued by discord, one insurgent group against another; then one faction got the upper hand and elected a new group of officers, which the opposing side said was illegal. The new head of Local 1703 was Sam Bonita. Over the next thirty days 4 people related to the mess are murdered.

Lippi is chosen to organize a new election of that local and calls for police protection at the nomination meeting. The next month an agreement is reached hiking the daily rate to $9 for miners working for the Pa. Coal Co. That seemed to be a good deal. In western Pennsylvania at the time miner’s daily wages were around $7.50. By comparison, loggers in the western states were making around $5 a day.

But apparently not everybody was happy with that deal. Sam Bonita, the newly elected and controversial president of local 1703 played down the deal to his 1,000 members and on Feb. 16, marched into UMW headquarters in Wilkes Barre with three of his strongmen looking for Lippi to discuss the settlement of the strike. Bonita, who had come to blows previously with Lippi’s long time friend and associate labor organizer Frank Agati, both of whom were instrumental in making the new deal in question, was not expecting to see Agati at the headquarters. Agati was also known as UMW president Capellini’s bodyguard.

Agati confronted Bonita and told him to “tell the truth” (to his union members about the deal) and said in Italian “I’ve had enough of this. Now I’m going to fix you.” Agati grabbed and punched the visitor, and may have made a motion that indicated he had a gun, and Bonita, known as “little Sam”, answered with ‘volley of gunfire', one bullet killed Agati, while Lippi and the others in the room dodged the other ’shots whistling by their heads’ and escaped.

Bonita was arrested the next day at his lawyer’s office. On Feb. 20, Lippi is a pall bearer for his friend Agati. Bonita claimed the shooting was in self defense and got 6-12 years for manslaughter.

The Wilkes Barre Evening News beautifully describes the courtroom scene that April:

The day before the Agati shooting Tom Lillis was shot six times on Railroad St. in Pittston. Lillis loudly opposed the newly elected of local 1703. Those two shootings set off a series of killings. February 18 Agati’s friends shot and wounded “Big Sam” Grecco as he walked with his wife to his home in Pittston. Grecco was a member of the grievance committee of local 1703.

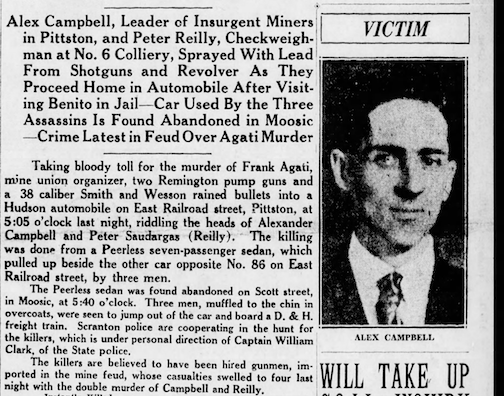

Then on February 28 Alexander Campbell and Peter Reilly were murdered in a drive-by shooting in Pittston:

Scranton Republican

Scranton Republican

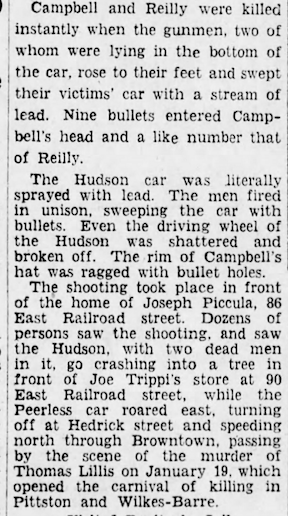

I can’t tell it better than the Scranton Republican report of Feb. 29, 1928.

The victim Reilly was the driver of the car Sam Bonita rode in to UMW

headquarters the day he shot Agati. Three or four years earlier both men’s

homes had been dynamited in response to their previous union feuds.

A Hudson, without bullet holes:

The Scranton Republican continues with a description of Pittston the night of the murder: “Behind locked doors the murder may have been discussed, but not in the streets. The Italian quarter has withdrawn into the expressive silence which always follows a murder. It is probably waiting for the next one."

That September (1928), Sam Bonita’s brother was shot and killed in a card game brawl at his home. They let Sam out of prison for the funeral.

Later that year, having survived all the shooting, Lippi adds to his activities in the community and gets elected vice president of the Exeter School Board. The school board it seems is also a subject of controversy over the years, and is prone to favoritism and under the table kickbacks. Teaching positions required a suspicious application fee of $500 in those times. That’s why my father ended up teaching music on the other side of the state instead of his home town.

The board required new leadership that year because the taxpayers ousted the sitting board. The school board also collects taxes from the coal mining operations within its boundaries. (In 1941 these coal company taxes amounted to $51,180, according to newspaper reports.)

The first part of 1930 is filled with labor disputes and labor disputes settled. Always, Lippi is in the center of the action.

In June, August Lippi, the newly elected Exeter School Board President, presents graduating seniors their high school diplomas, and in October he appears as a director on the annual condition statement of The First National Bank of Exeter. In December he is elected to a 6-year term as president of the Exeter School Board.Exeter is a town of about 4,800 between Wilkes Barre and Scranton.

Lippi’s is a life of conflict management, resolving problems like unmet payrolls, and urging workers not to join local illegal strikes; but he is also a star in the community with charity work and making speeches to local civic groups.

But not everybody adores him. Feb. 2, 1934, somebody threw a stick of dynamite onto his front lawn in protest of we don’t know what. The explosion blew out a few windows, and though ''the residents were unharmed it did cause them some ‘consternation.’ Dynamite is a key tool in coal mining for blasting through hard rock, and, as we have seen, it’s useful in getting someone’s attention.

Summer of 1934, Gene Lippi, brother to August, is appointed janitor to Exeter public schools at a salary of $110 per month. Top teacher salary at this time is $165.

June 1935, August Lippi, school board president, hands an academic achievement award in chemistry to Giulio Paci’s son, high school junior Bino Paci; and an award for achievement in the subject of algebra to my father Adrian Paci now in his senior year.

In the summer of 1936, janitor Gene Lippi’s salary is raised to $150 per month. In December, a petition is filed to oust the school board for refusal to do their duties and for filing an extravagant budget of $204,000. I think the petition failed.

1937 finds more union dust-ups and Lippi is 'assigned to investigate.’

In June he hands my father Adrian and his first cousin Renzo Paci their high school diplomas. Later that month he is re-elected to a 5-year term as trustee of the Community Welfare Federation of Pittston and vicinity. In November, he resigns from the controversial school board.

The next year a bankruptcy referee appoints Lippi and others trustees for the liquidation of Wyoming Valley (as that area of Pennsylvania is called) Collieries Company.

1938 finds more hubbub in the school board as republicans and democrats fight for control. The November election was a tie, and in the dispute that follows one republican vote was thrown out, but the republicans contend that there were 5 illegal democratic votes including one by Lippi’s sister Adele who didn’t even live in the area.

The 1940 census lists the August Lippi family household as containing himself and wife Lena, their children Ettore, 17, John, 15, Joan, 8; Lena’s sister Sue Fiorot, and their mother Regina Fiorot.

Lippi shows up in 1941 news reports as Secretary Treasurer of UMW district 1. In 1943, his son Ettore graduates from Cornell with a degree in architecture, making a break from the extraction industry. By 1950, Lippi’s children are grown and married.

The ‘40s and ‘50s were Lippi’s Cadillac and Lincoln years. July 1951, he was elected president of UMW district 1, and the outgoing president described him as ‘eminently fitted by integrity, experience, education, background and temperament.’ Local union membership at this time was estimated at 42,000, including 8000 retirees; but membership was going down.

He and his wife are active in their charity organizations. He lobbies state government on issues concerning anthracite coal use because the industry itself is in decline. The chief use of the coal is home heating.

In 1950 he graduated from Brooklyn Law School, and earlier, graduated from the University of Scranton with a business degree.

December 1954, he is now chairman of the board of the First National Bank of Exeter with deposits of just under $3 million. Long time friend George Daileda is head cashier, a position he has held for some time, and Lippi’s son Ettore, and Robert Dougherty are listed as directors.

Lippi is re-elected UMW district 1 president and begins a 4-year term starting April 2, 1957.

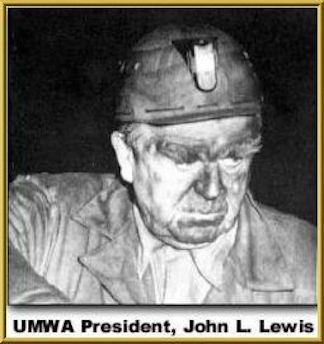

Things slowly degrade in the late ‘50s. The union’s welfare fund is in distress, pensions are being cut, and death benefits are in arrears. In December, Lippi goes to Washington to plead his case to John L. Lewis, president of the UMW and the "miner’s friend."

January 14, 1959, Lippi is now listed in the annual bank condition report as president of the First National Bank of Exeter; vice presidents are A.J. Minichello and Robert Dougherty; cashier George Daileda; among the directors are Ettore and A.J. Lippi (sister to August) and Robert Dougherty.

January 22, 1959, the bottom falls out of Lippi’s world when the roof caves in on one of the Knox Coal Mine Company’s shafts running under the Susquehanna river in a town nearby. Twelve men die and their bodies are never recovered. Rumors fly immediately, and Lippi is reported as being a stockholder in the Knox company, a charge he denies as he sets up a disaster relief committee for the families of the missing miners.

The Susquehanna river swirling into the Knox mine shaft

Rumors, and accusations concerning just who were the stockholders of the Knox company were met with denials by Lippi and now Exeter bank vice president Robert Dougherty. By February, a federal grand jury investigation is underway looking at violations of the Taft-Hartley Act which prohibit mine ownership by union officials, the FBI is investigating, and trouble spreads as the family of Lippi’s wife are called in questioning their relations with the bank and the mine. And the UMW is investigating their own as another UMW official is accused of getting a payoff from Knox company.

By March, the turmoil starts to take its toll on Lippi, he is admitted to the hospital with pneumonia. Later that month back on his feet, he stonewalls questions asked of him by a legislative committee, and after another 30 days of legal back and forth, and enduring his family being dragged into the mess with subpoenas for testimony, he is back in the hospital the first week of May.

Having recovered from that, in July he faces probes into his Exeter bank by the U.S. Attorney General’s Special Group on Organized Crime. Lippi’s indictment comes on August 7 for accepting a payoff of $10,117 from officials of the Knox Coal Company. Then came the involuntary manslaughter charges and warrants for arrest, and in, August 1959, Lippi is identified as a part owner in the Knox mine and he posts his first bond, $1000, after he waives a hearing before a U.S. commissioner. A conspiracy charge is added. Then Luzerne county weighs in with its own charges September 1, and the county’s indictments are upheld the first of December.

The next six months are filled with delay tactics. There is a change of venue for the trial, and by the middle of June, Lippi is in the Wilmington, Del. courthouse facing a charge of violating the Taft-Hartley act by owning an interest in a mining operation while holding a position in the miner’s union. Now the details of his involvement with Knox are slowly coming to light. Mrs. Sciandra, an owner of Knox, claimed she gave Lippi her Knox stock to hold as security on a loan.

“August J. Lippi, a peppery man of 59,” an AP story in the Delaware County Times reported, "who has spent all his working life in and around Pennsylvania’s hard coal mines, was convicted Monday (June 20, 1960) of bribery charges.” “Lippi said he loaned Sciandra $18,000 in 1945, because back in the 1920’s, when he was destitute, Sciandra grubstaked him several hundred dollars."

It later came out Lippi held 280 Knox shares, valued at one time at $450. That would be $126,000 collateral on a 15-year old loan of $18,000.

A second conviction comes down July 14 for involuntary manslaughter and conspiracy for hiding ownership in Knox. Bail this time is $5,000.

Now under conviction in federal and state courts, Lippi is nominated at the end of August for a third term as president of district 1 UMW. The union takes a hands-off position and Lippi continues as president. Union membership in the district is now (Dec. 1960) down to about 10,000. John F. Kennedy is elected president. In February Lippi avoids sentencing for his two convictions by winning a new trial.

In union business, the UMW abolished a $14,000 a year position in May ’61, and stated the president of the union’s district 1 would continue to receive his $17,000 annual pay.

Some time in August 1961, Lippi, at the pleading of my grandparents, my grandfather being his first cousin once removed, takes a minute from the chaos of his life and pens a letter to a nearby state college asking the admissions board to accept my application for admission despite my substandard high school grade average. And they did.

In December, the conspiracy charges were dropped, and early in January ’62 Lippi stepped down as president of First National Bank of Exeter, though he continued as director. Ettore, his architect son took over the bank’s top spot.

But it was all too late. Shortly before midnight Jan. 29, 1962 the FBI arrested Lippi in a Washington, D.C. motel on charges of violating the Federal Reserve Act. Earlier that day bank cashier George Daileda, who had worked at the bank since 1927, was arrested and charged for understating accounts and making false entries to cover checks written by Lippi starting in 1946.

Agents said at the time of Lippi’s arrest in Washington, he had his passport, a cashiers check for $30,000 drawn on his Exeter bank, and an itinerary for a South American trip. Lippi said the check could not be cashed without his wife’s signature and that it was to pay off a mortgage on his home.

Bail now is $25,000, and it is met by Lippi’s family by putting one of their houses up for collateral.

There were more charges, counter charges and number changes. The shortage at the bank goes to $440,000, and the bank goes to conservatorship under the U.S. Comptroller, the first time in 25 years that rule is used, and depositors are allowed to withdraw only 10% of their deposits. It was a short freeze. The Wyoming National Bank of Wilkes Barre soon purchased the Exeter bank.

To add insult to injury, Lippi’s Lincoln is repossessed in March, and the government accusers really like the tax evasion angle; the amount in question is now up to $80,000 corporate taxes on the Knox company. The alleged evasion tactics included padded payrolls and phantom salaried workers.

The conviction on 5 counts of tax evasion came down mid April (1962) for Lippi and Mrs. Sciandra as owners of the Knox Coal Co. And Lippi still faces trial for charges of personal income tax evasion of more than $67,000. Meanwhile, he continues conducting UMW business.

In September he and Sciandra make an appeal for a new trial on the tax evasion conviction.

By December the Lippi family really needed a little vacation. Lippi, his wife, and her sister and brother-in-law hitched a ride on a private plane owned by one of the local coal companies to Idlewild where they had planned to catch a jet to Chile for a two-week vacation.

However, the FBI didn’t see it that way and grabbed Lippi with $9,638 in his pocket as he got off the private Beechcraft. The rest of the family continued to their destination and came back after the first of the year. Lippi spent that Christmas in Lackawanna county prison in Scranton.

Lackawanna County Prison

Bail is now $150,000, and he makes it by putting up two valuable office properties in Wilkes-Barre owned by the family.

To polish off his disastrous year Lippi wrecked his ’61 Caddy late in the afternoon of Dec. 28 in downtown Wilkes Barre.

In January ’63, Daileda admits to perjury; and in April there is a drive-by shooting into Daileda’s home, wounding his 30-year old son in the left leg.

A piece of good news, for change, came in May when U.S. District Court acquitted Lippi of conspiracy and corporate tax evasion in the case of two other mines he and Dougherty were involved with as bankers to the mining companies. The government alleged they were part owners.

Lippi is now awaiting sentencing in the Knox tax evasion case, awaiting trial for the shortfall at the Exeter bank, and awaiting trial on charges of personal income tax evasion.

In July, Lippi’s name is mentioned as one of the industry officials instrumental in getting a $20 million government contract to provide anthracite coal for use in military bases in Germany. Tony Boyle is UMW president at this time.

The trial for charges related to the Exeter bank started early in November 1963. During testimony Daileda, the head cashier, was asked if he ever asked Lippi to put up money to cover his checks. Dialeda said he did, and Lippi responded “What the hell good is a bank if I can’t use it."

He was convicted of defrauding the bank of $38,977 on November 19, three days before the assassination of JFK.

Bail this time was set for $30,000, covered by his own home. Sentencing was postponed. In December, while attending a union meeting in Washington, he had a heart attack, from which he recovered.

Sentencing for the Knox coal company $80,000 corporate tax evasion case came down in mid-January 1964. He got three years time, a $5,000 fine, and was ordered to make restitution of all delinquent taxes. He gave notice of an appeal and remained free under bond for the time being.

Now he still faces sentencing for the tax evasion charges related to the bank, and his personal taxes.

In the bank case appeal Lippi denied all Daileda’s testimony and said he always used his own money to pay his debts. Though the government contended the bank had a loss of $400,000, it was unable to link Lippi with more than $38,000. In May 1964, his motion for a new trial was denied and he was sentenced to five years and fined $10,000 for conspiring to defraud the former First National Bank of Exeter.

The sentences of three years and five years were to run together. The net effect added two years to the 3-year sentence and increased the fines.

That July, two convictions hanging over his head, he announced that he is a candidate for re-election as president of UMW’s district, and is involved in lobbying for the use of coal to heat a local post office instead of gas.

In September, the court authorizes him to leave the jurisdiction to attend the international UMW convention in Florida where he and other union officers wrote up a new wage agreement with hard coal operators.

He was re-elected president of UMW district 1 in January 1965 by 7,192 votes, and later that month filed an appeal for the conviction related to the bank. The appeal was denied in March.

Also in March, Lippi’s son John was appointed UMW secretary-treasurer, and, the announcement said, will continue in the position of international representative; a position he has held since 1951.

That summer Lippi took his appeal to the supreme court twice to no avail. The court didn't hear the case, but Lippi did have a minor victory that month when he got two more local post offices to heat their buildings with anthracite coal.

In October, George Daileda, the Exeter bank head cashier awaiting sentencing for his conviction of bank fraud, has a heart attack and dies at age 58.

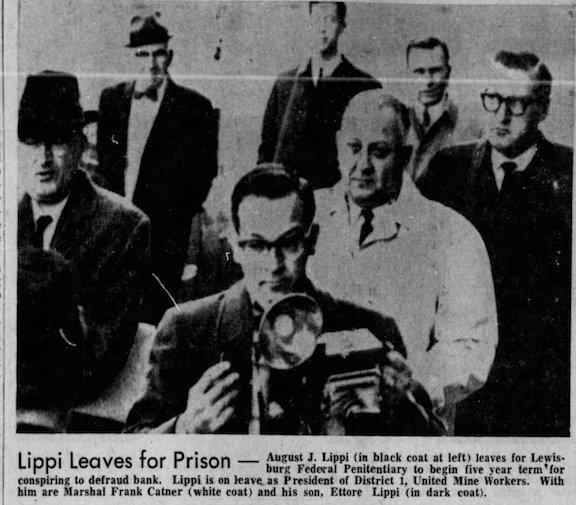

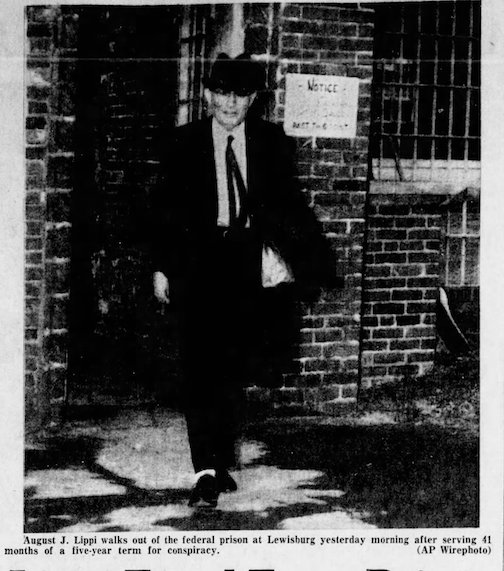

Lippi’s lawyers appeal for shorter jail time because of his health, and he is granted a leave of absence from his union post a day before he was transported on Dec. 21, 1965 to the Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary to begin his five year term at age 65.

Hazelton Standard-Speaker - Nov. 6, 1965

Hazelton Standard-Speaker - Nov. 6, 1965

The courts and the lawyers keep churning. About the same time he begins his jail term the government drops criminal charges in his personal tax evasion case, but the IRS still wants the $67,000 it says is owed.

The next year, 1966, the IRS gets its numbers together by November and is now looking to get from Lippi $327,334 back taxes for a nine-year period. Three months later the Justice Department chimes in with its demand for $15,000 in fines that have been levied; in March 1967 Lippi and his wife file for bankruptcy. In September, a parole request is denied. And in December, the IRS files a $1.17 million tax lien against the late George Daileda for 1957 through 1963.

A second parole request is denied in April 1968, but Lippi’s son John is lobbying union people to support a nomination of Lippi to his former post as president of the UMW district 1 and it was reported nearly all the 46 local unions are for the nomination despite the opposition of the international officers; and by July the support is unanimous in 22 of the 46 locals.

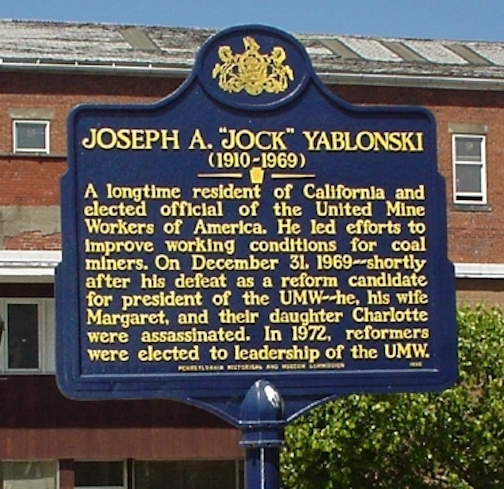

Late in July, UMW chief Boyle appointed a three man commission to investigate the district’s voting setup and warned that Lippi was not qualified for the presidency because of his violations. Joseph Yablonski was one the three investigators. Lippi was again denied parole and in early August John Lippi was fired by the UMW board along with his sister Adele who also worked for the union organization, and a provisional trusteeship and government was imposed on district 1.

The younger Lippi contended that he was an elected official and could not be fired, and the elder Lippi filed suit against the acting UMW president seeking to have his name placed upon the ballot. The UMW trusteeship cancelled the December elections, but the Lippi contingent continued their quest. The UMW countered by merging several other union districts into district 1, and in February 1969 sold the district 1 UMW office building to Wilkes College.

Lippi was released from Lewisburg on March 20, 1969, though he was on probation for another five years. His suit to be placed on the UMW ballot was dismissed in April, but on the home front the IRS wrote off his $327,334 tax bill as uncollectible along with Robert Dougherty’s corporate tax bill of $122,258. In August the bankruptcy referee discharged the Lippi’s from bankruptcy and were released from all debts and claims and their estate is valued at $3,000.

Yablonski, now running for the top UMW job, trashed Lippi in one of his campaign speeches in October. He said “I know how Joe Kershetsky, Mart Brennan and Gus Lippi desecrated this organization. They used to brag that they never count the anthracite votes-they weigh them. They didn’t care how the miners voted.”

Lippi's end came May 11, 1970, a month shy of my graduation from the U. of Md. and the birth of my son.

Putting his life together like I just did from news reports is, in a way unfair, because the low points were the most newsworthy. It’s a portrait of Lippi the UMW figure. Missing is Lippi the man, interacting with his family, cutting his grass on Saturday, doing things not dressed in a business suit. In his defense he was involved in many charities, and his wife and her family were innocent bystanders and were close to my grandparents and my aunt. Nevertheless, it’s quite clear the job gave his life meaning.

Here in his obituary with the unflattering photo it states he started the Exeter bank in 1917 which is an example of how bad the newspapers’ reliability is. He did not start the bank in 1917 when he was 17 years old, I’m not sure when he joined the bank. I have him appearing on the bank’s board October 1930 which was the first appearance of his relation to the bank in the newspapers I searched.

.jpg) I never met “Mr. Lippi,” as he was referred to in my family, but I know that my father and aunt, my grandparents, and my grandfather’s siblings interacted with him mostly for weddings and funerals, though he lived in a parallel universe from all of them.

I never met “Mr. Lippi,” as he was referred to in my family, but I know that my father and aunt, my grandparents, and my grandfather’s siblings interacted with him mostly for weddings and funerals, though he lived in a parallel universe from all of them.

Sometime in the late 1950’s Lippi hired my grandparents as janitors for the UMW office in Wilkes-Barre. Now that I look back on it, the gesture may have been one of magnanimity, but also it put the keys to the office in the hands of trusted people. My cousins and I, when we visited my grandparents, went with them as part of the crew.

To our young minds the Lippi office was world apart from the busy stove, grape arbor, and vegetable garden of the Paci home in Exeter. The office was on a quiet tree-lined Wilkes-Barre street, in a red stone mansion, with airy rooms, thick carpets waiting to be vacuumed, big crystal ashtrays, and fat curtains on the windows; it had a cathedral-like aura. The cleaning routine with my grandparents was all business: empty trash cans, ash trays, vacuum, swish apparent dust and be gone. Not a lot of talking. And, don’t touch any papers.

It seems Lippi’s driving force, the thing that he felt gave him a pass on all the shady deals and funny business at the bank, was that he was the miner’s angel. As long as he was in charge of the union, men would have jobs and, in that, he had taken care of his family.

He was Machiavelli’s untouchable prince of his Wyoming, Pa. valley, until he wasn’t. At some point, perhaps in the late ’40s he could have ‘gone straight’, could have started following the rules, not abused his bank privileges; he could have run for public office given his notoriety. But there was some cultural tic that made him cling to the fast and loose way of life. Maybe it was the culture of corruption in the mining business, as some have called it; a business with slim profit margins, and many easy ways to cut corners.

Whatever it was, it cost him and his family a decade.

Posted by ronpaci at March 6, 2017 5:02 PM