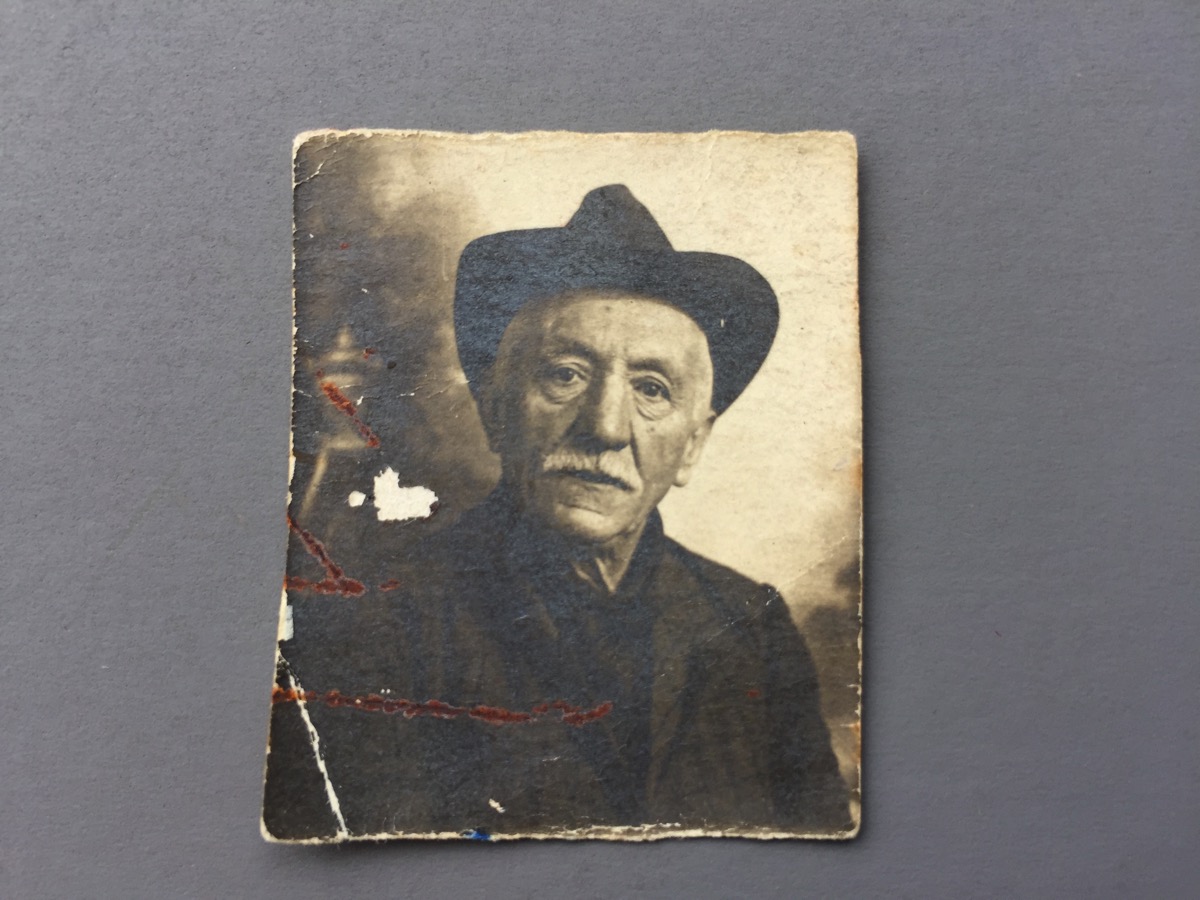

'povero vecchio'

Cireglio

Cireglio

July 17, 1931 Cireglio, Italy - Adamo Paci woke up to another hot, dry day in the Tuscan Apennines overlooking the medieval city of Pistoia in the valley below. There is a drought this year, crops are weak, the economy is weak. Prime Minister Mussolini has made every thing a battle: the battle for grain, the battle for the lira, the battle for land, and the battle for births to supply a growing army.

In a mind twisting game Il Duce is trying to make Italians feel like they are joined together in a national struggle for independence so as to disguise the fact that his Facisti government is failing, and most Italians are living in unpleasant poverty compared to their neighboring countries. The letters home from those Italians who emigrated reinforce that fact, and the money they send home is a line item on the national budget.

Pistoia in the valley below

Pistoia in the valley below

Our Adamo is not up for any battles, and he’s not happy. At 83, his mind is filled with the past. his wife, Argene, has been gone for two and a half years; son Giulio died in April, and daughter-in-law Clotilde Bartoli, wife of Adamo’s son Ugo, has also died this year.

This July Friday in 1931 Adamo wrote a post card to Cino Paci, one of his three sons living in Exeter, Pa. With a fair hand, he wrote 16 lines in black ink with his fountain pen revealing a regretful man, well worn down from his years.

Eva and Corinna post their greetings on the front of the card

His post card was in response to a card he received from Cino, the contents of which are unknown. Maybe Cino felt like reaching out since the death of his brother Giulio in April. Whatever Cino wrote got him a verbal spanking from his father.

Adamo’s career as a tailor has long been over. We don’t really know about that part of his life in Cireglio, his small mountain village of about 500 people, most of whom had their own sewing kits and knew how to use them. We don’t know what he did day to day: Did he have a garden? Did he have chickens and rabbits? Did he have a grape arbor? We do know from a previous letter he was a drinker. I wish I knew what he was drinking.

il ‘sfortunato' padre Adamo

He may be thinking life has passed him by, but he’s not alone this year. Of the 10 children he had with his second wife Argene (Lippi) 4 or 5 are still nearby; of the others, 3 are in the U.S., 2 are dead - one died as child, one in WW1.

He had two children with his first wife Maria Leschi: Dante, a bachelor, also in the U.S. with his two brothers and one sister; and Ugo, who may now be living in Switzerland.

Living in Cireglio at this time were son Pacino, age 45 who had a small grocery store, and daughters Corinna 46, Eva 51, Rosa 37; Agnese 43. There may be as many as 16 grandchildren moving around his world.

Arnaldo, the child of Giulio and Assunta who had some developmental problem and was left behind when they came to America, is in that mix, maybe still living with Adamo. After Adamo’s death he lived with Pacino and his wife Bianca, and later with Pacino’s daughter Fernanda, who at this time is about 5.

Argene, Rosa, Adamo, Arnaldo, and baby Piero(?) 1925 - written on back of photo

In the postcard he addresses Cino and his daughter in law - my grandmother Fiorina, whom he probably knew as she and her family were also residents of Cireglio - and his grandchildren - my father Adrian and his sister Fedora, whom he has never met and never will because this is the year Adamo will die.

Cireglio 17 - 7 - 931

(it is typical for Italians to leave off the ‘one’ when writing the year: 931 instead of 1931. saves ink.)

Caro figlio Nuora e Nipote,

Dear son daughter-in-law and grandchildren

O ricevuto tua Cartolina

I received your card

dal Posto ave Var’ a Sonare (to sound)

from the post office(,)

a domandato ha so …(illegible)

ask myself

-ra se avivi (avevi?) scritto e mi

ditti si a scritto eppoi

if you had (ever) written to me…

i don’t have a firm grip on those first few lines but he seems to be saying getting a post card from Cino was a shock, and he rhetorically asks himself if Cino had ‘ever’ written to him.

Makes you wonder if Cino ever did write home since he and his half brother Dante stepped off the La Provence onto Ellis Island on January 18, 1914, seventeen years before Adamo picked up his pen to write this card.

Cino had been a little busy trying to make a go of it as a foreigner in America with a language issue. Luckily there was a tribe of Italians in Exeter, Pa. waiting for him, many from his home town. The ‘old country’ was like an evaporating dream an ocean away for many of these immigrants with full, busy lives, and mouths to feed.

In July of ’31 at the Schooley Avenue Paci compound of two homes, Assunta, with Giulio gone in April, was now alone with her five children; though Fernando is 19, and Lummy 18, Lydia, Bino and Renzo are under 16. Fiorina and Cino are in the home at the back of the property with five-year-old Fedora, and Adrian, who is 11. Dante, it seems, floated around the neighborhood living at times in one or the other Schooley Avenue homes.

This July morning Adamo’s mind was filled with octogenarian thoughts of his life as he mulled over the poverty of letters from his children in America. He hadn’t seen his late son Giulio for 23 years, daughter Emma for 19, Dante and Cino for 17. Except for Pacino, who returned to Italy after the war, he will never see any of the other emigrants again.

Cino, Dante, and brothers Giulio and Pacino got out of Italy just in time to miss the disaster of WW1. Cino finished his service in the Italian army in December 1913, and the next month was on the boat. The others were already here.

Not all the sons of Adamo and Argene escaped WW1. Their ninth child, Lemmi Adrian, never came back from the fighting.

In October 1913 Cino and his one year younger brother Lemmi Adrian were pall bearers dressed in their Italian military uniforms at the funeral of their uncle Pietro Lippi. Pietro was a brother of their mother Argene Lippi Paci. The Lippi’s were from the village of Castello di Cireglio. Pietro was well known and ran a big foundry in Pistoia. I’m still working on his story.

Cino and Lemmi Adrian were probably buddies. A colorized photo of Lemmi hung in the Schooley Avenue house until the end. Now it’s in mine. I would like to have seen my grandmother’s reaction when my grandfather, apparently, chose the name Adrian Lemmi for my father. The brother and the son both were killed at 24 years of age, the brother in WW1 and the son in WW2. Lemmi Adrian served in the Italian 83rd infantry division, and Adrian Lemmi in the 84th U.S. infantry. I have seen children named after ill-fated family members a number of times now, it produces a grimace on my face every time.

Lemmi Adrian Paci 1892-1917

Thinking about Lemmi Adrian’s fate these past few weeks has dragged me into the black hole of WW1 history. We have two facts about him: the pall bearer scene, and the Italian army report of his death in April 1917 as an infantryman in the 83rd regiment, district of Pistoia, which notes that he died of a disease as a prisoner of war. Could have been Spanish flu, typhoid, cholera or any of the other things ill-treated prisoners of war were subject to.

We American relatives don’t know where he is buried.

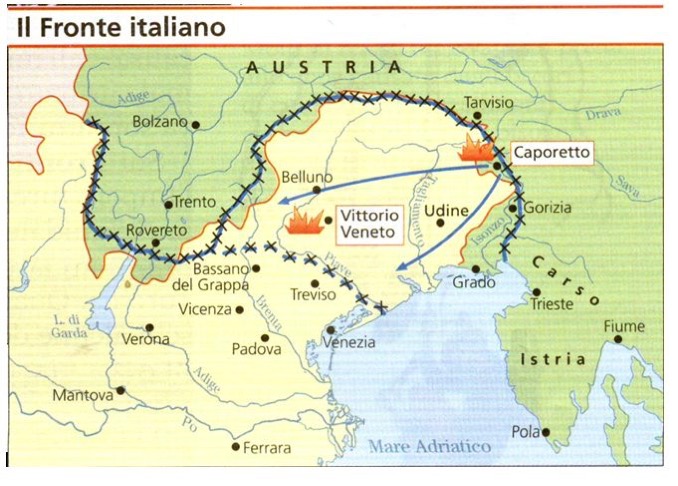

Not to go down this road too far, but the Italian effort in WW1 was concentrated mainly in the mountains north of Venice along the borders of Slovenia and Austria, ‘il fronte Italiano’. The Italians had been allied with Germany, Austria, and Slovenia in a deal known as The Triple Alliance since the 1850’s. But, when the war broke out in July 1914, Italy held back. They weren’t ready militarily or economically, and were in secret negotiations with both sides for nearly a year. Finally the Allies offered Italy a slice of southern Austria - Trentino-Alto Adige area - as a prize if the Allies won the contest. That won them over and they cancelled the Triple Alliance pact.

This adventure saw many familiar names. Young Mussolini was, a bersaglieri, an elite mobile unit that wore black feathers on their helmets He served about nine months until he was wounded in 1917 and went back to the propaganda business as a journalist.

Mussolini,the bersaglieri

Mussolini,the bersaglieri

Hemingway was there in June and July 1918. Lemmi Adrian was gone by then. Papa Hemingway got his book A Farewell to Arms out of it, plus a bunch of shrapnel in his legs, and notoriety when he was wounded in July 1918.

He and American author John dos Passos signed up as ambulance drivers as did several other recognizable names including Walt Disney and writers W. Somerset Maugham and E.E. Cummings.

The Great War, as the Europeans called it, was the number one romantic adventure of the time for many young men, until it wasn’t.

Hemingway in a Fiat ambulance

Hemingway in a Fiat ambulance

Hemingway just had to get there but couldn’t get in on the fighting because of bad eye, so he joined up as a driver with a private company running the ambulance fleet at the front. Dos Passos was more of pacificist, but as a writer he too just had to be there, not necessarily to do any killing, so he hooked up with the same ambulance group. Their Fiat ambulances developed a bad reputation for breaking down, and eventually were replaced with Model T Ford ambulances when the Red Cross took over the ambulance business.

The famous desert fox of WW11, Erwin Rommel, was on the scene at the Italian front and got the Pour le Merite for his brilliant quarter-backing in this little game.

Adolf was on the Western front as a young, very serious, no-nonsense soldier.

...oh oh oh it’s a lovely war

who wouldn’t be a soldier, eh?

Oh it’s a shame to take the pay...

Another photo from this era in my collection is this photo below of young soldiers and their knives. It was a novelty to me until I discovered that the knife thing was a universal pose in historic photos of the Italian outfit known as Arditi - the daring ones. (Ardire means ‘to dare’) The guitar player with cigarette is Milano Trapassi who survived the war and married my grandmother’s sister Santina. The Arditi were like the German stormtroopers and received special hand-to-hand combat training.

Milano Trapassi with guitar

Until I get more info on Lemmi Adrian’s precise unit and its movements, the best I can picture is he was probably captured in 1916 in one of the late battles of the Isonzo campaign. Italian soldiers were an unhappy lot. There was a lot of hiding from the draft both in the South and the North. The country was still a collection of diverse regions with their own dialects. To add to the confusion each regiment called up recruits from two different regions, then sent them to a third for training.

The Austro-Hungarians had similar diversity issues, but they had fortified the high ground in the mountains before and during the early stages of the war and were ready. The Italians were sort of ready, but they had more bodies than hardware outnumbering the opposition by about three-to-one. Life was cheap.

There were twelve battles over two years along a 400 mile front following the Isonzo river north of Venice. The Italians got about 10 miles into Slovenia and then it was a stalemate with high casualties on both sides, especially for the Italians climbing, dragging enormous guns with mules and muscle up the rocky landscape and facing the 8mm Schwarzlose M7 machine guns pointed down at them. There was trench warfare here like that on the western front, but here the ground was rock not mud and digging trenches was problematic.

The final battle of that campaign was at Caporetto in the fall of 1917 when the Germans finally appeared on the scene to back up the Austro-Hungarian effort and turned the tide on the Italians.

arrows show the advance of the Austrio-German forces after the battle of Caporetto

arrows show the advance of the Austrio-German forces after the battle of Caporetto

In each battle, especially at Caporetto, large numbers were captured by both sides and that’s how prisoner of war Lemmi Adrian ended up buried somewhere across the Italian border, probably near the hospital where he died, in what eventually became known as Yugoslavia.

The Italian records of WW1 are extensive and I suspect we can probably get another clue as to exactly where he is buried it we could find where he was taken prisoner, or the name of the hospital where he died, though it may be an unmarked grave.

Research on POWs in WW1 has increased in recent years.

Italian prisoners of war numbered about 600,000 over the years of the war. When it was over Italian political and military powers swept the fate of the captured under the rug wanting to move on quickly from that period. Damnatio memoriae.

I wonder if Adamo or any of the family in Italy ever knew the whereabouts of Lemmi’s gravesite.

……………………………………..

Adamo’s letter continues:

ha saputo che ai comprato l’automobile…..

i know that you bought a car

We don’t know exactly how Adamo discovered Cino’s new purchase, but many of the people Cino knew in Exeter were from Cireglio. A new car in 1931 was big news and was probably mentioned in many letters home.

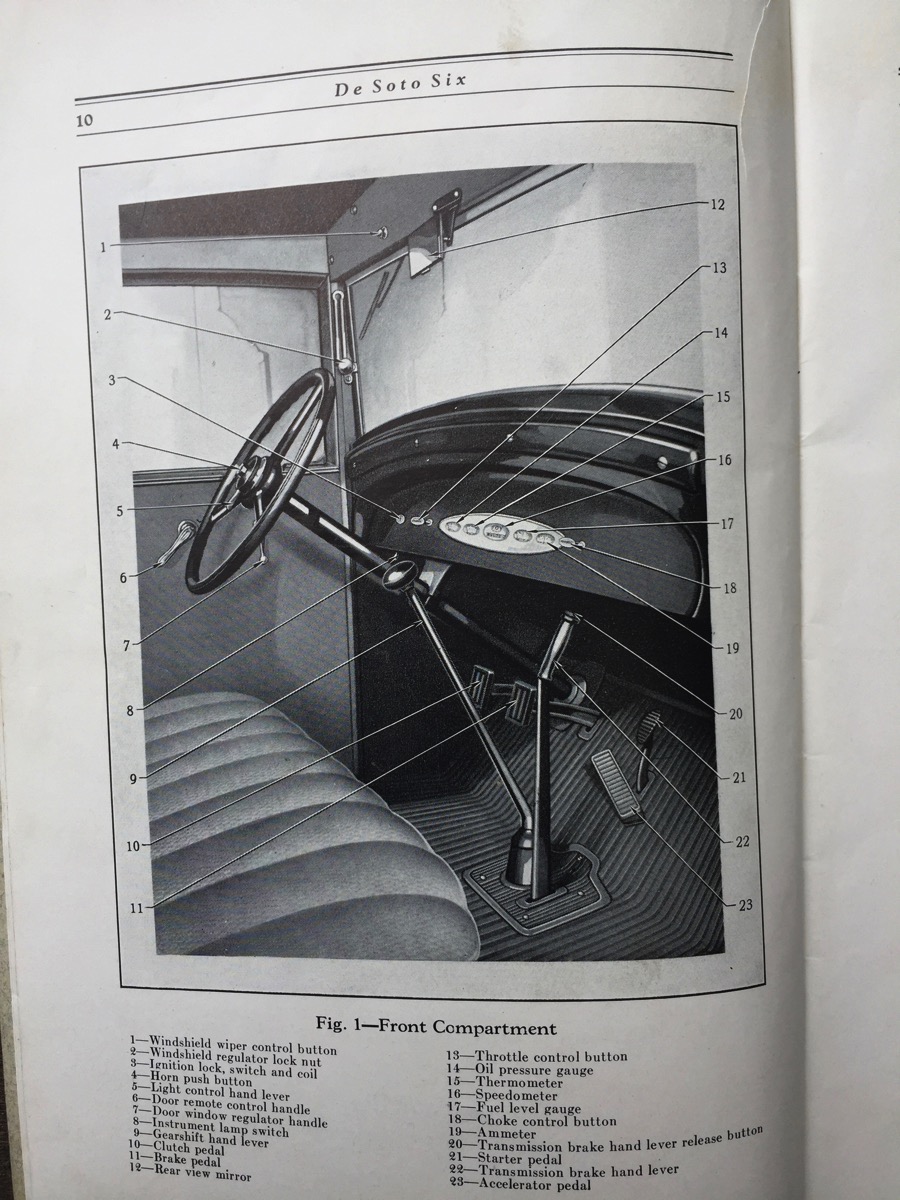

1931 De Soto in 1931

1931 De Soto in 1931

In the photo is Lydia (Giulio’s daughter) near the rear window, the others in the back are identified as Adrian and Liberty (daughter of Emma Paci Calvani). plus one mystery person in shadow. Fedora, as the favorite of my grandfather, had the honor of the front seat.

So Cino buys a brand new De Soto probably for about $850 at the height of the depression. There is a lot we don’t know about these guys. I know at this time they had the cabin at Spring Brook so that may have been a factor in getting a car, that and the general necessity of keeping up with the times. And, he had other income from his band which was going strong at the time, probably playing a couple times a month. The band was in Exeter’s Memorial Day Parade that year.

One of the features of the depression was a distrust of banks which led to people hoarding cash. Maybe Cino was turning his cash into hard goods.

1931 De Soto Six: 67 horsepower, three on the floor, wire wheels, a pedal above the gas pedal was the starter.

The manual emphatically reminds the new owner to always lock the car. This is the depression, remember.

The postcard continues:

…….ho piacere

i’m glad

che vi…godiate tutti

that everyone’s enjoying themselves

pur che non pensiate

without giving a thought

al padre che vi oh

to the father who had

portato all’ epoca di guadagnare

carried (them) all these years

un figlio solo, eve e

only one son (Pacino?), Eva and

Corinna, gli altri nulla al

Corinna (have given him any attention), from the others nothing to the

povero vecchio

poor old man

godetivi e divertetiri e

enjoy and have fun and

salute vostro sfortunato

regards your unfortunate

padre Adamo

father Adamo

Unless he’s pulling Cino’s leg with a little old-fashioned guilt tripping, the ’sfortunato’ one must have thought by having 12 children he was insuring his future with dedicated subjects. He didn’t plan on wars or the siren call of America where the ‘money grew on trees’ according to his son Giulio.

Adding the ’s’ prefix to an Italian word like ‘fortunato’ reverses it meaning often to the negative.

………………………………………...

So that’s it. I stuffed this postcard into an unrelated envelope for safekeeping when i brought it home from Fedora’s collection a couple years ago and forgot about it until it turned up in the December housecleaning. I’ve been mulling over the 1931 world of Adamo and the Paci’s since the card turned up, and that led to the Lemmi Adrian business and WW1.

William Shirer in The Rise and Fall of The Third Reich says Mussolini made the mistake of seeking to make a martial, imperial great power of a country which lacked the industrial resources….and, unlike the Germans, the Italians were too civilized, too sophisticated, too down to earth to be attracted by such false ambitions’… “the Italian people, at heart, had never, like the Germans, embraced fascism. They merely suffered it, knowing that it was a passing phase, and Mussolini toward the end seems to have realized this…..”

And in the Caporetto book author MacDonald reiterates that: “Most (of the Italian soldiers) had little understanding of the reasons for the war and saw it as another ‘signore’ adventure.”

…………………………………..

photo by RM Auctions

photo by RM Auctions

Since the core subject of the postcard is l’automobile here is the 1939 Alfa Romeo 6C Mussolini bought for his mistress Claretta Petacci. They enjoyed it for a few years until they were picked up near the Swiss border trying to escape to Germany near the end of the war in 1945 and were shot by Italian partisans. Their bodies were brought back to Milan where the two of them, and some others, were famously hung upside down in the square.

The car was confiscated, but later somehow was grabbed by a clear-minded American soldier and shipped to the U.S., used by his family until it broke down, and then stashed in a barn in New Jersey. Now, having changed hands a couple times and fully restored, it’s valued at $2.4 million.

And De Soto’s like Cino’s have sold for $8000 to $12,000 at recent auctions.

and i leave you with that….

-rp

Farewell to Arms, Ernest Hemingway (1929).

The Ambulance Drivers: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and a Friendship Made and Lost in War, James McGrath Morris (2017)

Caporetto and the Isonzo Campaign: The Italian Front 1915-1918, John MacDonald and Zeljko Chimeric (2011)

Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, William Shirer, (1960).

Posted by ronpaci at 1:11 PM